In the early 2000s, every government leader who visited Estonia was proudly given a tour of the chamber of the government at Stenbock House, to witness the row of flat-screen monitors behind which Estonian ministers made important decisions completely paperlessly and which had become the image of Estonia as a digital nation. As the years moved on, these visits became increasingly quaint, because a government whose work took place behind computers was no longer remotely unique, though out of civility, our high-profile guests still expressed great admiration. In 2013, our government finally gave up their desktop computers and the awkward tours to see computer monitors stopped, although the story of a paperless government still continues to be told to visiting dignitaries.

The state of the image of Estonia as a digital nation is somewhat similar: we are trading on past glories and the fruit of good past decisions, yet we need more than that in order to stay competitive. Electronic elections are a clear international landmark, and e-residency is also an interesting idea. In other words, there are several things we are doing well even today, however the overall level of our e-governance is lagging behind. Meanwhile, elsewhere in the world, this field is developing rapidly, and Estonia has to constantly step up its efforts in order to retain its image and remain a global trailblazer in e-governance.

Working daily in the fields of software robotics and software quality and development, we see a number of simple ways to ensure the continuance of Estonia’s digital success story and to further increase the efficiency of our public sector IT solutions.

The first step involves creating a central public code and knowledge repository and setting up a community of specialists around it. Estonian government agencies constantly commission various information systems with miles worth of software code, which could easily be reused by other agencies in their solutions. Take, for example, login systems, where currently the same components are recreated again and again. Thus, we propose aggregating the related knowledge and software in a single hub that also employs people that can advise public (and perhaps even private) sector entities on which functionalities already exist and do not need to be re-commissioned. If done correctly, this could reduce costs related to code management, updates and the commissioning of new information systems by as much as a third.

Secondly, there are a number of important areas where more cooperation between state agencies in commissioning and developing software solutions could save both time and money. For example:

o infrastructure: cloud services, hosting, high availability, implementation of the concept of data embassies;

o software architecture: creating a centralised databank of best practices;

o security: developing centralised security testing capabilities and offering the service and free consultation to all state agencies.

Thirdly, updating existing information systems or creating entirely new ones should not be done based solely on existing processes and legislation. We should also consider future needs and opportunities, as well as changed user expectations. There is a need to make it possible to update legislation internally – officials generally know where the bottlenecks are, but currently lack the means to do anything about it.

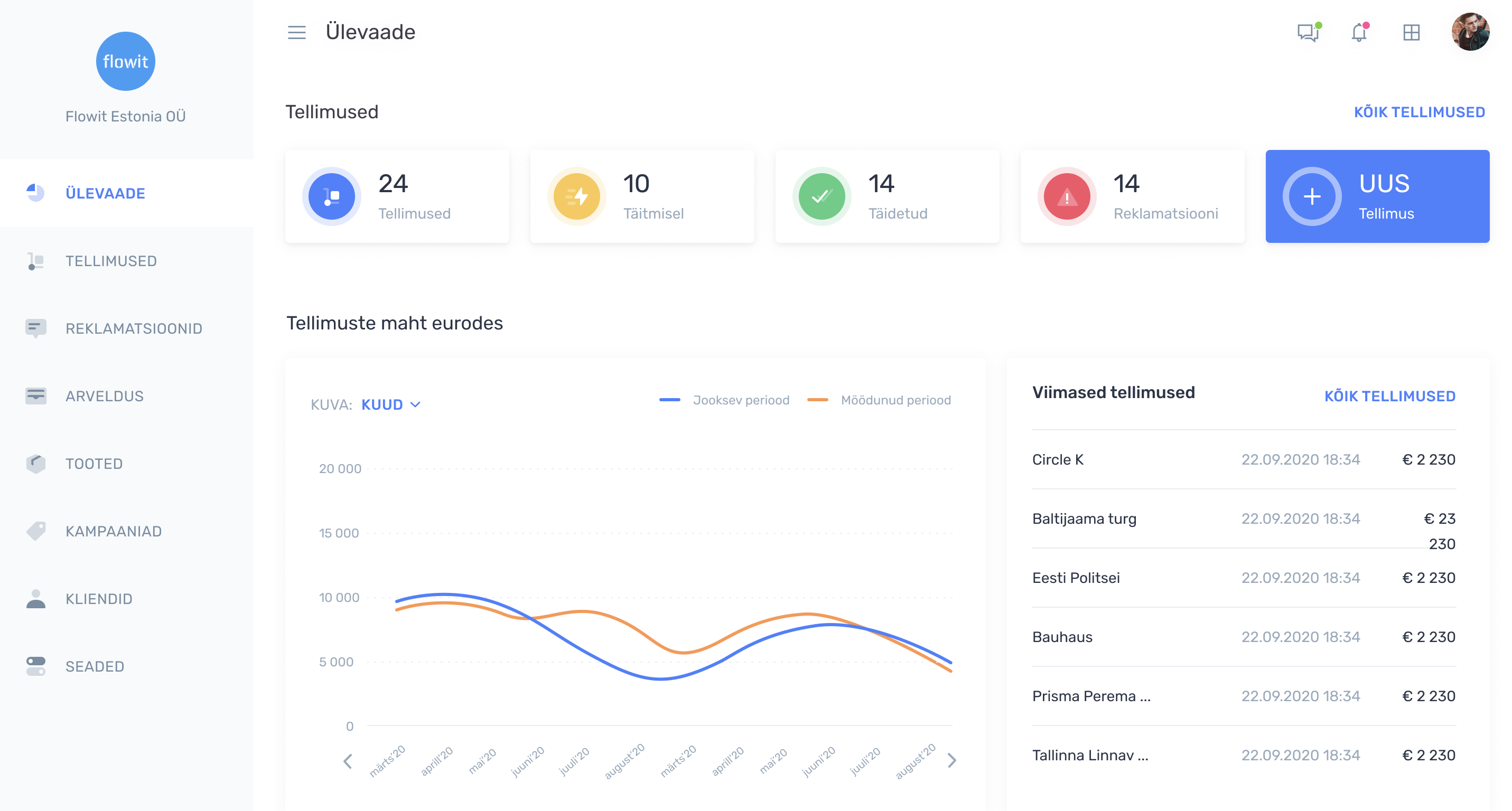

The fourth major aspect concerns user experience (UX) design and user interface (UI) design, which need to be an integral part of all state IT system development projects. Much of the criticism currently directed at our state information systems is related to poor UI and UX design. Whenever the relevant specialists are not included in development projects, we end up with unintuitive and completely antiquated applications. Today, using our state information systems often resembles filling out paper forms. It should not be necessary for every agency to start each new information system project from scratch – the reasonable solution would be to provide centrally managed technical style guides and samples of good user-friendly e-service design.

Fifth, when creating state information systems, software quality should be priority number one. Business-end representatives are unable to carry out sufficiently thorough software testing. Most projects require involving an impartial quality assurance partner – this way the contracting party could also be made responsible for their failings, which would help eliminate problems at source. Similarly to how construction supervisors are hired to monitor construction projects, the state should also commission supervision in software projects.

Sixth, e-services and e-governance should be objectively assessable and measurable. This requires creating a quality assessment model for e-services that would enable a variety of metrics to be used. For example, a similar model has been developed in Finland. The results of such e-service assessments should be made public and available to everyone. This would increase the transparency of our e-services and hopefully provide an impetus for developing and implementing even better e-services.

Finally, all state agencies, ministries and local governments should commit to identifying all activities and processes that are currently wasting the time of our civil servants. Work with Excel tables, data processing and analysis, manual transferring of data from one system to another, preparation of reports – these are all jobs that should be automated. However, this requires a firm decision to implement automation at all levels and eliminate pointless work. In Scandinavia, this is a part of the daily work of state agencies, and while in Estonia we are taking our first steps in robotic process automation (or RPA) in the private sector, the potential benefits in the public sector would be significantly greater. Automation is the sole path towards a lean government, as only through automation can we increase labour efficiency and focus on what is truly important.

This article was published as an opinion piece in Eesti Päevaleht on 30.07.2018. Read also: http://epl.delfi.ee/news/arvamus/juhan-madis-pukk-seitse-sammu-mis-muudavad-loodriks-jaanud-e-eesti-jalle-liidriks?id=83187649